DeSantis Launched His 2024 Campaign Off His ‘Landslide’ Re-Election. The Numbers Tell a Different Story.

AP Photo/Charlie Neibergall

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis (R) used his 2022 re-election as a springboard to launch his presidential campaign, touting his “landslide” win over Democrat Charlie Crist as a mandate for his policies and one of the few bright spots for the red team in an otherwise brutal midterm election cycle for the GOP. DeSantis’ nearly 20-point margin of victory earned him a lot of fawning headlines, but a closer look reveals it to be a mirage, pantomiming greater electoral strength than he ever actually possessed.

Ever since DeSantis’ presidential campaign ended in an embarrassing sputter after getting curb-stomped in Iowa by the four-times-indicted ex-President Donald Trump, there has been a schadenfreude-infused parade of columns bashing him for his “too-online” communications strategy, awkward personality, chaos–plagued PAC, and indulgence in far-right culture war issues that alienated non-Trump Republicans while failing to woo the MAGA faithful.

But this entire time, from the first rumors that DeSantis wanted to run for president to the campaign’s ignominious end, the narrative that the governor won in a “landslide” and “turned swing state Florida red” has rarely been questioned. With Trump losing to Joe Biden in 2020 and the expected “red wave” failing to materialize in the 2022 midterms — especially with so many Trump-endorsed candidates stumbling — an outspoken Republican who trounced his opponent by double digits had obvious appeal to conservatives licking their post-election wounds. DeSantis was one of the few Republicans with a “W” on the 2022 scoreboard and presented himself to voters as someone who could reverse the losses the party was having under Trump.

And the numbers themselves were objectively stunning — at least on the surface, anyway.

According to the official tally by the Florida Division of Elections, DeSantis had 4,614,210 votes, or 59.37%, while Crist trailed far behind with 3,106,313, or 39.97%. That’s a margin of victory of over 1.5 million votes, nearly 20 percent. It’s not surprising many headlines the next morning used the word “landslide” — especially when compared to DeSantis’ 0.4% squeaker win over Tallahassee Mayor Andrew Gillum in 2018. In that race, DeSantis got 4,076,186 votes (49.59%) to Gillum’s 4,043,723 (49.19%), and a recount was needed to get it finalized.

However, when framed in the context of several key facts about Florida political trends, DeSantis’ 2022 margin of victory plummets down much closer to earth.

It was a Republican margin of victory, not a special DeSantis margin

DeSantis’ 2022 performance was closely matched by all four of the other Republicans running in statewide races:

Senate: Marco Rubio (R) 4,474,847 votes (57.7%)

Val Demings (D) 3,201,522 votes (41.3%)Attorney General: Ashley Moody (R) 4,651,279 votes (60.6%)

Aramis Ayala (D) 3,025,943 votes (39.4%)Chief Financial Officer: Jimmy Patronis (R) 4,528,811 votes (59.5%)

Adam Hattersley (D) 3,085,697 votes (40.5%)Agriculture Commissioner: Wilton Simpson (R) 4,510,644 votes (59.3%)

Naomi Esther Blemur (D) 3,095,786 votes (40.7%)

In other words, the governor’s win wasn’t a unique voter preference for him individually, but a reflection of the overall Republican voter advantage in registration and turnout. By 2022, the contested 2000 Bush vs. Gore race that came down to a few hundred votes in Florida was over two decades in the past, and Florida was unquestionably a red state. It’s not shocking when a Republican wins a deep-red congressional district in Amarillo, Texas or when a Democrat wins in even deeper-blue San Francisco, California; in 2022, the Florida results weren’t actually as shocking as they were treated.

DeSantis benefitted from Florida’s rightward shift from decades of Republican work

Florida Republicans’ 2022 collection of big statewide wins (and GOP supermajorities in both the state house and senate) came after a decades-long shift to the right in voter registration numbers, a process that preceded DeSantis’ entire political career and was set well in motion before he was able to exert influence over the Republican Party of Florida (RPOF) as governor.

For years, Florida Democrats clung on to a substantial voter registration advantage even after Republicans managed to wrest majority control of the legislature in the mid-1990s. That began evolving due to multiple factors, including broader population shifts, older Democrats dying off (a more influential factor in retiree haven Florida than in other states), “Dixiecrats” who had more centrist/conservative views than the national Democratic Party changing their registration to Republican, removing inactive voters from the rolls, and an exploding number of voters (especially those under 35) registering as independent or no party affiliation (NPA).

And there was a colossal amount of work and money invested by RPOF and other Republican organizations.

As NBC News national politics reporter Matt Dixon detailed in his recently-released book, Swamp Monsters: Trump vs. DeSantis―the Greatest Show on Earth (or at Least in Florida), the voter registration statistics are the “most obvious — and most dramatic” illustration of “Republican dominance in Florida,” and he spelled out how the numbers steadily shifted from a 700,000 voter advantage for Democrats that helped Barack Obama win Florida in 2008 against John McCain to “a 257,175-person registration advantage” for Democrats in 2018 and a “roughly 300,000-person voter registration advantage” for the GOP in 2022.

That nearly 600,000-person shift in voter registration from 2018 to 2022 on its own accounts for well over one-third of DeSantis’ margin of victory over Crist.

A major acceleration of the shift from blue to red occurred during now-Senator, then-Governor Rick Scott’s (R) tenure. A billionaire hospital executive, Scott poured over a hundred million dollars of his own money into his two gubernatorial races, including substantial investments in voter registration and get-out-the-vote initiatives. As Dixon notes, this led to DeSantis being able to run in a state where the Democrats’ voter registration advantage had fallen nearly 55% since Scott’s first race in 2010 and more than 40% since Scott’s 2014 re-election campaign.

One longtime Florida GOP consultant anonymously grumbled to Dixon that it was “frustrating” to see DeSantis take credit for decades of other Republicans’ work. “Florida didn’t turn red because of you, motherf*cker. It was twenty years of hard work,” said the consultant. “It started with Jeb [Bush] and continued with Rick Scott, who himself raised $1 million for voter registration programs.”

To be fair, DeSantis might deserve partial credit for improving the size of his own voter base. He engaged in very public outreach promoting his Covid policies to unhappy conservatives in blue states to move to the “Free State of Florida” — but people have always moved to Florida for many reasons, like the weather and lack of a state income tax. Since the state’s admittance into the United States, there has never been a U.S. Census that didn’t show double-digit population growth for Florida.

No one was excited to vote for Charlie Crist, not even Charlie himself

Crist is an infamously singular creature in Sunshine State politics. He’s a former Republican governor who bailed on the GOP after Rubio skunked him in the 2010 GOP Senate primary, switched to independent and lost again to Rubio in the 2010 general, did a brief stint as a billboard and TV spokesmodel for a personal injury law firm, switched to Democrat, ran for governor against Scott in 2014 and lost, ran for Congress in 2016 and won, and then ran against DeSantis in 2022 and got absolutely clobbered.

As far as I can tell, Crist is the only Floridian to lose statewide races with the complete trifecta of Republican, Democrat, and independent party affiliations. Quite the unfortunate accomplishment.

He was branded a hapless loser long before he faced DeSantis on the 2022 ballot, and there’s strong anecdotal evidence that many Florida Democrats have never fully viewed him as one of their own after decades as a Republican. There is that old adage about victory having a hundred fathers and defeat being an orphan; Crist might have been embraced with more enthusiasm if Democrats hadn’t kept seeing his name atop so many electoral disappointments.

Crist himself didn’t help matters; as much as DeSantis has been pilloried this past year for his awkward interactions with voters, Crist struggled to look like he could even fake enthusiasm for voting for himself. The former governor known for his perma-tan, bright white smile, and encyclopedic memory for names ran a sad shell of his previous campaigns. Outside of one rare bit of feistiness at their only debate when Crist challenged DeSantis to commit to serving four years and not abandon the state to run for president, memorable moments for Crist were few and far between, leaving no catalyst to spark donor or voter interest.

Rick Wilson, a longtime Florida Republican strategist who left the party to oppose Trump with The Lincoln Project, described Crist as the “single worst option for the Democrats” in 2022 because “he was a spent force in the Republican party before he was a spent force in the Democratic party,” a candidate who “had no constituency whatsoever” but “just enough name recognition to win a primary” against Nikki Fried, the former Agriculture Commissioner (and last Democrat to win a statewide race in Florida).

Fried put up a spirited fight in the primary, but couldn’t get traction against Crist’s name recognition advantage — and neither state nor national Democrats were willing to invest in the race for her or any other potential challenger. Fried has since gone on to chair the Florida Democratic Party (FDP), relishing the opportunity to be an outspoken thorn in the side of Florida Republicans — and has seen her party finally score some victories in flipping the Jacksonville mayor from R to D and winning a hotly-contested special election in House District 35 earlier this month.

But even if Crist hadn’t run or some wild twist of fate had helped Fried win the 2022 primary, it’s still highly unlikely she would have fared much better against DeSantis in the general. The money and infrastructure imbalance was just too overwhelming.

Gruesomely outmatched financially: “Like Florida State playing Savannah State”

It cannot be emphasized enough how much of a financial advantage DeSantis had in 2022. Florida is a massive state that takes all day to drive across and millions upon millions of dollars to buy ads in our various media markets. DeSantis smashed all previous records for gubernatorial campaign fundraising in 2022, pulling donations from all 50 states, and used that mountain of cash to obliterate Crist like a nuclear bomb would a mosquito.

Florida campaign finance records show DeSantis’ direct campaign spent $25,756,294.20 as compared to Crist’s $18,105,000.45, but the direct comparison of their campaign expenditures only tells a sliver of the story. It’s the PACs where this contest gets utterly gruesome.

The Friends of Charlie Crist PAC spent $14,227,704.07, and DeSantis’ similarly-named Friends of Ron DeSantis PAC buried him more than sevenfold by spending $99,896,061.66. (Side note: following the trend of DeSantis’ hostility to transparency in government, his PAC changed its name after the election to “Empower Parents PAC,” and for some reason, the state campaign finance reports for 2022 retroactively changed the PAC name in all its listings, making it harder to find.)

That massively lopsided monetary imbalance also happened with the various party organizations, with FDP ($21,006,352.27) and the Florida Democratic Legislative Campaign Committee PAC ($10,891,752.06) together spending less than the Republicans spent just with their state senate PAC, the Florida Republican Senatorial Campaign Committee ($39,122,739.82). Add in the Florida House Republican Campaign Committee ($24,240,400.24) and RPOF’s overall state spending ($143,179,075.76), and you have the Republican party groups spending over $200 million in the general to the Democrats’ $30 million. And that was after the Republicans had spent nearly $14 million on ads promoting DeSantis during the primary election.

That party money wasn’t all for DeSantis, obviously, but RPOF has long taken advantage of state campaign finance law allowing “three-pack” ad buys, promoting three candidates instead of just one. Political parties can buy television, radio, and mail ads at a nonprofit rate, cheaper than the candidates’ campaigns directly, and the gubernatorial candidate at the top of the ticket is often the designee for one of those three spots.

An analysis by AdImpact reported an RPOF three-pack for DeSantis and two cabinet races spent $68.86 million on ad buys during the 2022 general election, averaging over $6 million per week. Crist’s PAC plus an FDP three-pack that supported him and two legislative candidates only spent $12.63 million total.

And then there was the controversial decision by the Republican Governors Association (RGA) to spend nearly $21 million dollars — nearly one out of every four dollars spent — to support DeSantis, despite the polls showing “he didn’t need a dime of help,” as one Trump adviser “heavily active” in the 2022 midterms told Dixon. This led to grumbling from Republicans in other states, like Kari Lake supporters in Arizona who watched her lose to Democrat Katie Hobbs by a razor-thin 0.6%. The RGA spent less than half in Arizona than it did in Florida; an Axios report described the Lake campaign’s TV presence as “paltry.”

“Republicans were motivated to run up the score to help DeSantis in 2024,” longtime Democratic strategist Steve Schale told Mediaite to explain the strategy behind spending so much money on a race that DeSantis was always going to win.

Schale, who lives in Tallahassee, said the DeSantis vs. Crist election was “like Florida State playing Savannah State,” referring to FSU’s tradition of scheduling out-of-conference small college opponents as sacrificial lambs (that’s a fact, not an critique; my alma mater UF does the same thing).

Everyone expected DeSantis to win easily, said Schale, “the question was always the margin,” and the millions of unneeded dollars flooding the state meant that DeSantis’ team could essentially “say anything they wanted to say without worrying about the opposition,” who had no money to answer. “Can’t whine about it, that’s just what it is,” was Schale’s verbal shrug, and he commented that this gave the Republicans the ability to run “messaging ads,” like the much-mocked (but amusing to DeSantis’ online fans) “Top Gov” ad portraying the former JAG attorney as a fighter pilot à la Tom Cruise’s “Maverick” film character, and the somehow even more indulgent “God Made a Fighter” ad that ran right before the election.

“You don’t do that when you’re fighting over actual policy positions,” said Schale. He added that had California and New York Democrats approached the 2022 midterms with the same “run up the score” mentality as Florida Republicans, the Democrats might not have lost their majority in the U.S. House. (This would have also prevented the Kevin McCarthy vs. Freedom Caucus drama over the speakership, not to mention possibly blocking serial fabulist George Santos from getting elected in the first place, but I digress.)

“The idea of [DeSantis] as a giant killer is just false…they blew Charlie out of the water financially,” was ex-Republican Wilson’s take. “It wasn’t even merciful. It was insanity levels of spending.” He scoffed at DeSantis (who went to Yale on a baseball scholarship) touting his 2022 win as being “electorally born on third base and bragging when he landed on home plate.”

Not only did the red team massively outspend the blue team, it could have been even worse. By Election Day, both Crist’s campaign and PAC account were bled dry, but DeSantis’ PAC still had more than $90 million left in the bank. DeSantis would eventually transfer the majority of that money to his presidential campaign PAC, Never Back Down (a move that drew a complaint filed with the Federal Elections Commission by an ethics watchdog group), but it was looming there ready to blast in case any Crist allies tried to balance the scales even the tiniest bit.

Can’t win if you don’t play

The Democrats’ problems in 2022 weren’t all Crist’s fault. Biden pretty much abandoned Florida in 2020. After Trump won the state in 2016, the Biden campaign, undoubtedly influenced by the shifting voter demographics, viewed the state as a game that was too expensive to even play, much less try to win.

The campaign’s calculus proved to be correct — Biden was able to win without winning Florida — but forfeiting the Sunshine State removed hundreds of millions of dollars from the political ecosystem that would have otherwise been invested by the Biden campaign, the DNC, and various PACs in voter contact, list building, messaging, and get-out-the-vote efforts across the state.

With Florida’s highly mobile population, the quality of any voter list quickly deteriorates, and by the time 2022 rolled around, the Democrats had gone four years without talking to Florida voters.

There were several 501(c)3 and 501(c)4 progressive groups active in Florida, but they diverted already-scarce resources away from FDP and other official party organizations and their nonprofit status means they can’t recruit only Democrats for registration or outreach, can’t campaign for Democratic candidates individually or for the party slate, and can’t give their lists to Democratic campaigns. These organizations can go to areas where they expect the overall population to lean Democrat, like college campuses or metropolitan neighborhoods with deep-blue voting history, but they can neither target nor advocate directly as a candidate or party can, and their work leading up to the 2022 election was unable to have a measurable impact.

Beth Matuga, a veteran Democratic Party operative, has long held a deeply cynical view of these nonprofit groups, lamenting to Dixon that they “have no accountability” and she’s never seen evidence that their claimed field operations are actually able to turn out voters for the Democrats.

Different story when the playing field is less lopsided

Tom Keen’s win in the HD 35 special election was cause for rejoicing among Democrats, especially the Florida House Democratic Campaign Committee (FHDCC), which dropped over $541,000 into the race. Florida Republicans were distracted fending off frostbite in Iowa during the last snow-covered gasps of DeSantis’ presidential campaign, and the FHDCC had the funds to hit a meaningful saturation point with advertising (I live in a nearby district and saw numerous Keen ads on TV and online) and to organize an enthusiastic gang of elected Democrats and volunteers to knock on doors.

Matuga, FHDCC’s general consultant, spelled out the path to success in a post on Schale’s blog. She effusively praised State Rep. Fentrice Driskell (D), the FHDCC chair, for “breaking caucus fundraising records left and right,” an arduous task that gave the organization the resources it needed to start a voter contact program in the primary. FHDCC stayed neutral until Keen won the primary, but those months didn’t go to waste as they updated contact files, identified likely Democratic voters, encouraged vote-by-mail signups, and engaged in messaging.

After Keen won the primary, Matuga wrote, the FHDCC deployed a targeted paid canvassing program that knocked on a stunning 68,000 doors (three times the total number of people who would end up voting in the special election) to urge Democrats to vote early or by mail and were able to compete with Republicans in ad buys. According to Matuga, the FHDCC “spent about $1.2m” and her best “guesstimates” based on media buys were that the Republicans “spent somewhere between $2m and $2.5m.”

“[W]e were grossly outspent as usual. But we weren’t obliterated,” Matuga emphasized, arguing that Florida Democrats “can win when being outspent 2:1 or 2.5:1…[b]ut we CAN’T win being outspent 4:1” or more (as the DeSantis-Crist race was).

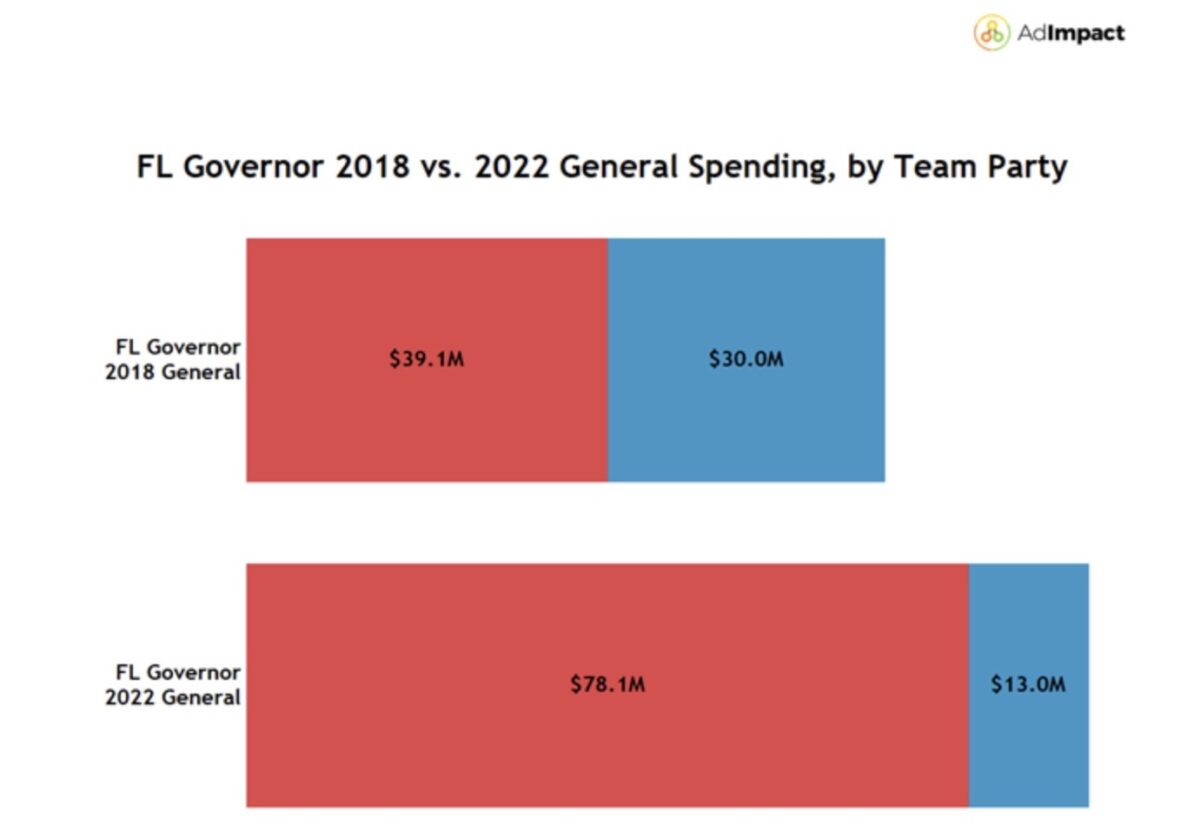

The past two gubernatorial elections support Matuga’s argument. According to AdImpact, Republicans spent $39.1 million to the Democrats’ $30 million in the 2018 general, a ratio of slightly less than 4:3. That’s within the “parity or close to it” Matuga wrote can put races within Democrats’ reach. Getting outspent by about $10 million, Gillum was only 32,463 votes short of being Florida’s first Black governor. In 2022, the Republicans spent six times what the Democrats did, and Crist never stood a chance.

Image via AdImpact.

Mediaite asked Schale how he thought the DeSantis-Crist election might have gone if there hadn’t been such a vast disparity in expenditures. “Had the spending been closer to parity,” replied Schale, “2022 would’ve been a four, five, maybe six-point race.”

That’s still a victory for DeSantis, and a comfortable one. But a five-point win wouldn’t have been nearly as alluring to conservatives reeling after their “red wave” dreams went up in smoke. Unfortunately for Republicans who hoped DeSantis could rescue the party from Trumpian drama, his 2022 win was not so easily transported north against opponents who would fight back.

Have a tip for us? tips@mediaite.com